From Trails to Avenues

The area surrounding the Milwaukee Avenue Historic District served as a resting place along the trail from the Falls of St. Anthony to the cliffs of Fort Snelling. As the City of Minneapolis grew, the trail was replaced by railroad tracks, which later expanded into extensive rail yards that fostered the development of nearby industries.

The emerging industrial base, the extension of streetcar routes along Franklin and Minnehaha avenues and the relatively sparse early settlement of the area all provided the background for the controlled housing development that would later be known as Milwaukee Avenue.

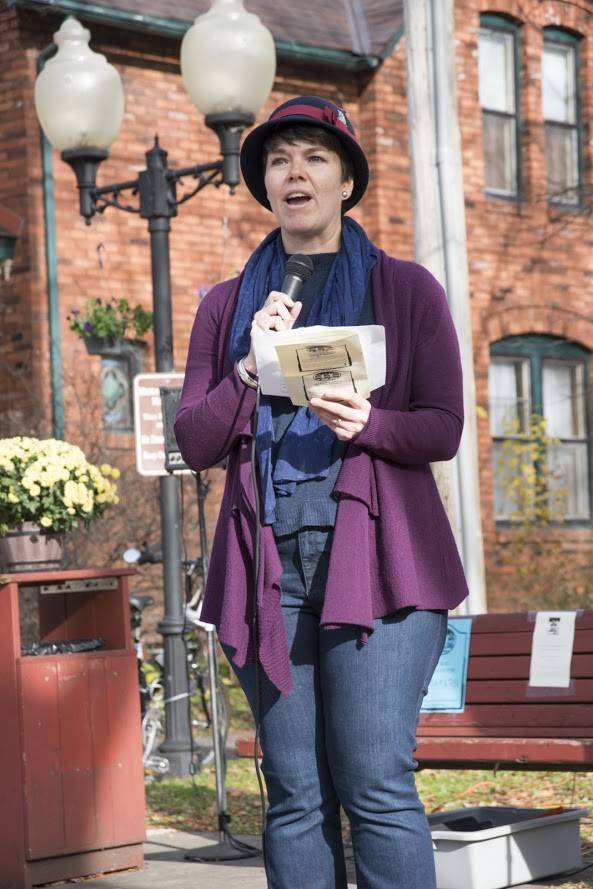

Working Man’s Roots of New Urbanism

Milwaukee Avenue Historic District

Built: 1883–95

Developer/Builder: William Ragan

Listed on National Register of Historic Places: May 1974

The earliest example of a planned workers’ community in Minneapolis, 22nd 1/2 Avenue (later known as Milwaukee Avenue) attracted workers of Scandinavian and East European descent, who worked for the nearby Milwaukee Railroad shops and yards and other industries.

Built on quarter-lots, these low-cost vernacular houses are framed with timber, clad in brick and have gingerbread decoration. Today, they evoke the current paradigm of “New Urbanism,” with its emphasis on medium-density housing, inviting porches and proximity to various urban resources. However, the original 1880s configuration actually reflects the developer’s chief motive: maximizing profit.

People-Power Preservation Pays Off

In the early 1970s, the City of Minneapolis housing authority planned to raze 70 percent of the houses in a 35-block area known as Seward West. It was a gambit to address blight and “renew” urban housing stock.

True, many homes along Milwaukee Avenue had suffered neglect and deterioration. But visionary neighbors recognized the integrity of the original houses, which led them to establish a new organization: the Seward West Project Area Committee.

To fight “The Man in City Hall,” this committee formed a development plan that emphasized historic preservation, and it designed a comprehensive site plan to save these homes and add appropriate new housing infill. That this four-block area exists today is a tribute to their moxie and might.

What’s New and What’s Re-new?

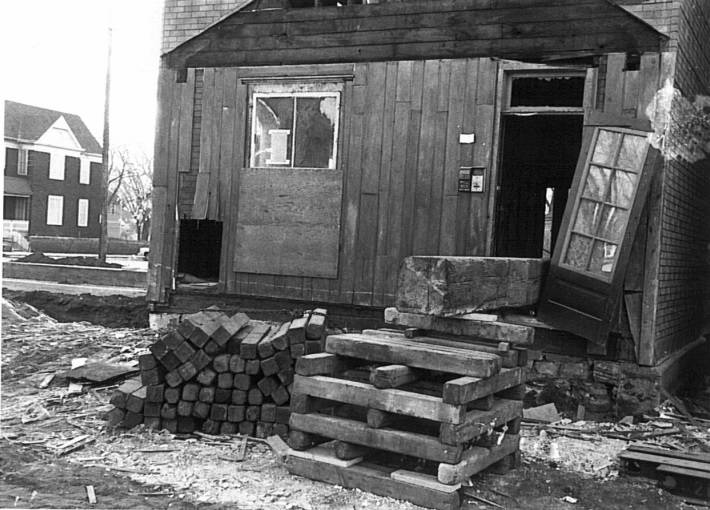

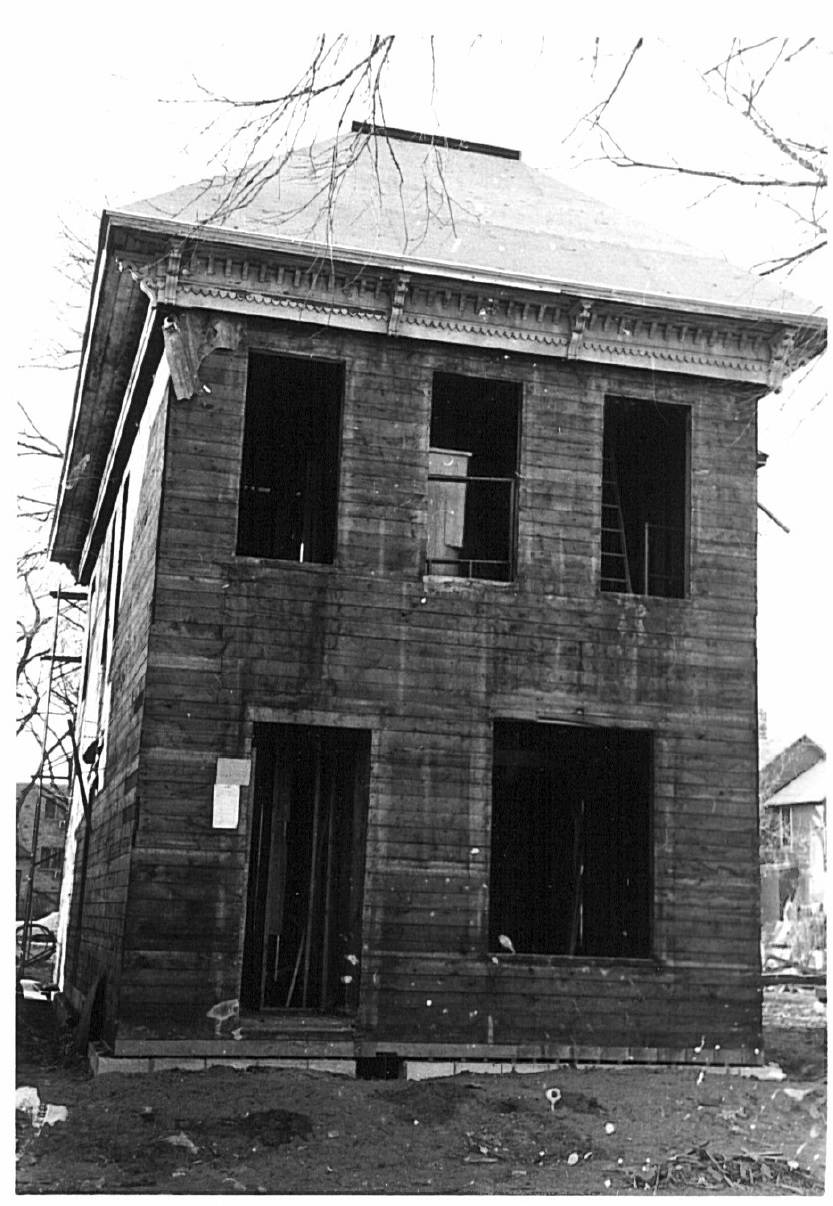

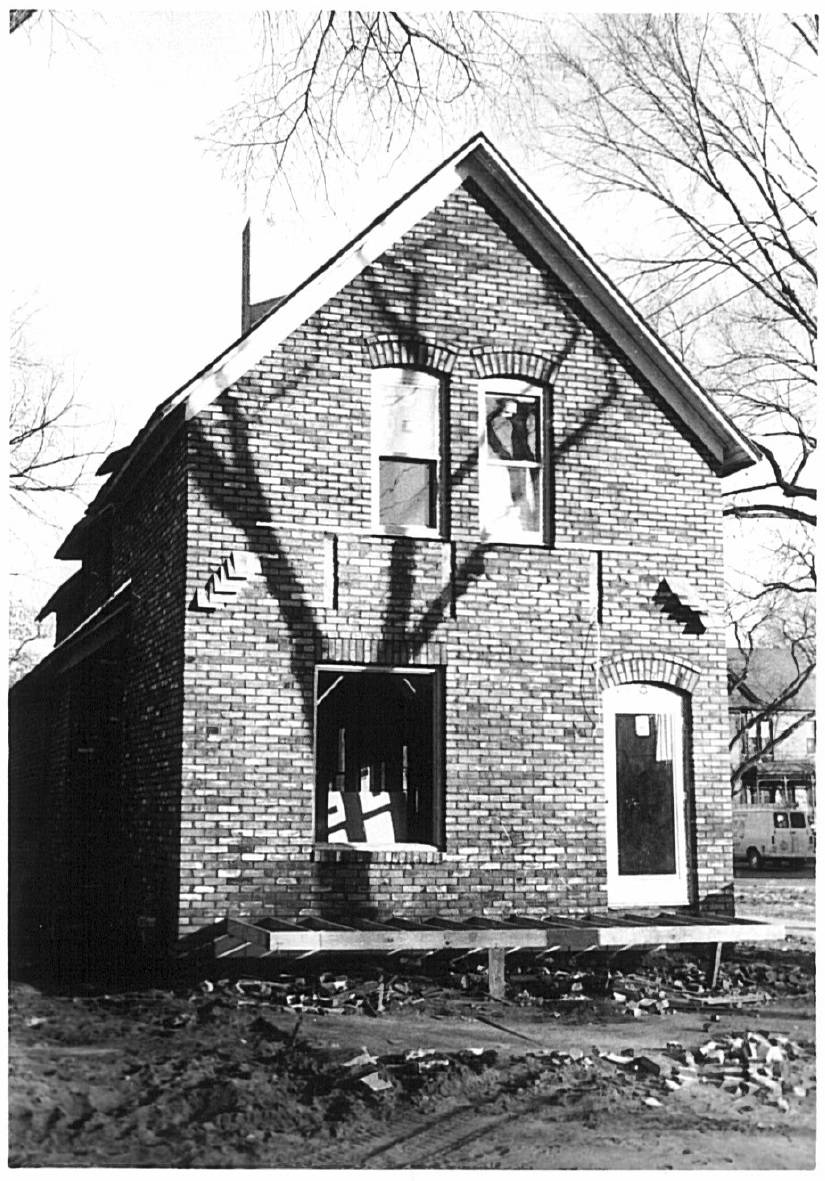

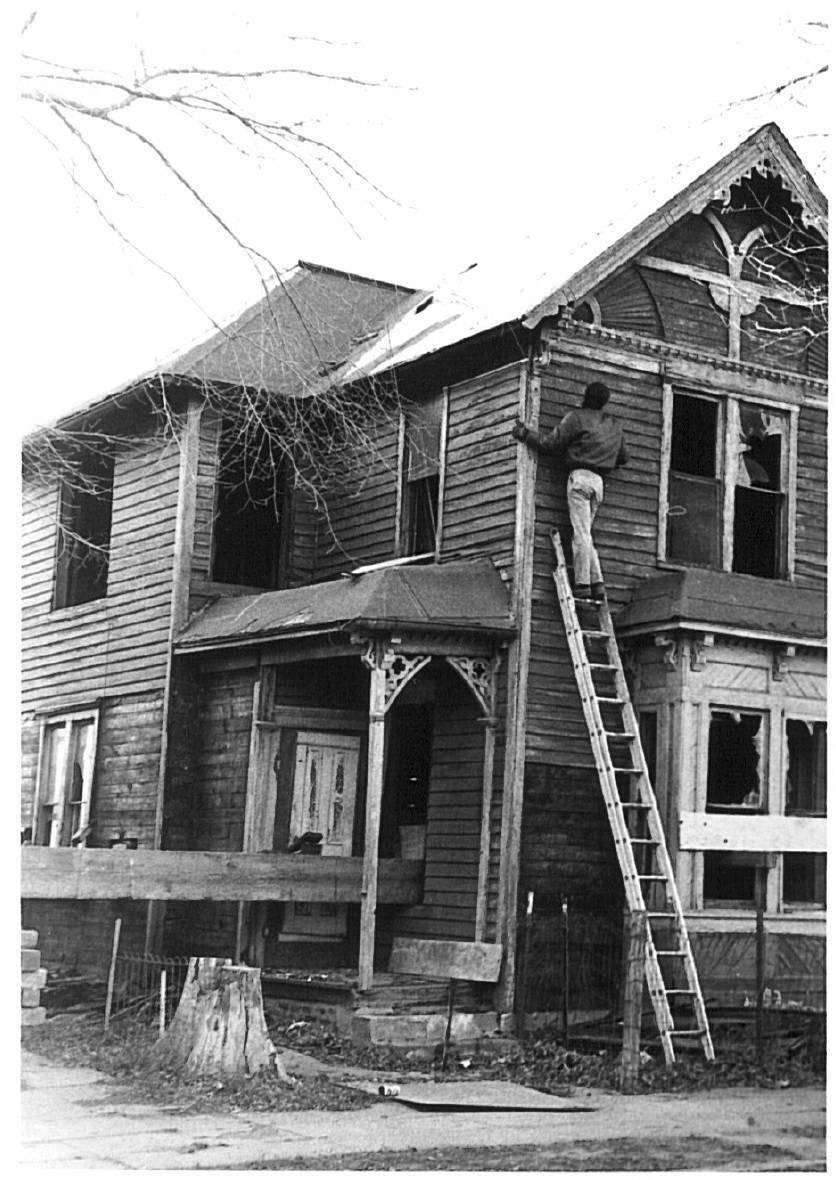

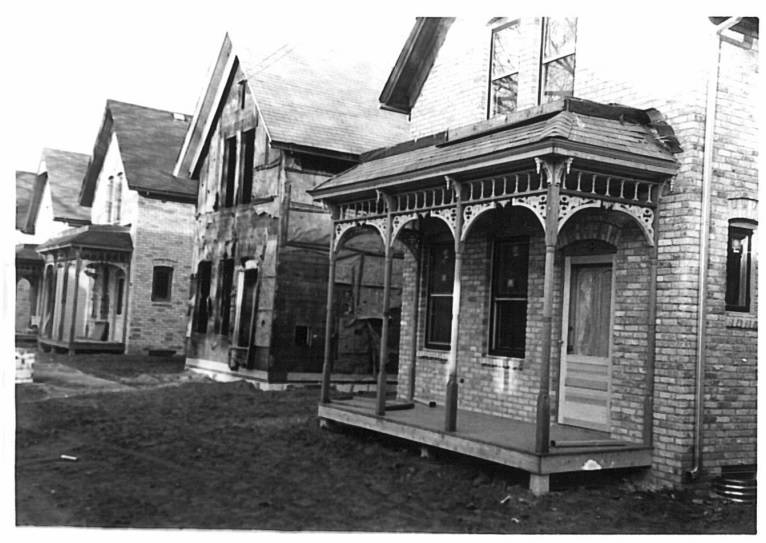

Led by the Seward West Project Area Committee, architectural plans directed rehab contractors to:

- Salvage what existing materials they could

- Lift up the houses to add foundations

- Install new mechanical and plumbing systems

- Strip exterior stucco-clad brick

- Paint and/or recreate damaged walls to resemble the original structures

- Rebuild porches with replica gingerbread woodwork

- Create new interiors to the owners’ specifications

Eleven houses on Milwaukee Avenue were eventually demolished and replaced with newly built historic replicas, and one house was moved onto the avenue from an adjacent street. The rest, however, were preserved and rehabilitated. As a final stroke of genius, the narrow street was converted to a pedestrian mall.

Why Is Milwaukee Avenue Architecturally Significant?

Milwaukee Avenue houses represent a “common man’s architecture,” which proliferated from copybook plans made popular in the late 19th century. However, the extensive use of sand-colored brick, the flat-arch window treatment and the regular (and somewhat severe) geometry is reminiscent of the immigrant German-style residences of the late 1800s found along the upper Mississippi River valley.

One of the primary reasons the historic district gained entry to the National Register of Historic Places is its rare concentration of worker’s residences of similar style. Most historic districts spotlight residences of the rich and famous—the lumber barons of Minneapolis and railroad tycoons of St. Paul, for instance—and overlook those of immigrant laborers who contributed so much to the growth of urban Minneapolis.

What Do the Historic Houses Have in Common?

The houses on Milwaukee Avenue are constructed of brick veneer on timber frame. This characteristic contributes to the historic district’s unique quality. Few of the residential areas built up during the second half of the 19th century in Minneapolis resulted in the construction of such a significant number of contiguous brick houses.

What’s more, the houses share common architectural treatments: uniform roof slopes, uniform separation on lots, modified flat-arch windows and open front porches with minimal applied ornamentation.

Today, to maintain the district’s historical integrity, any plans to alter the exteriors of member homes must first be approved by the MAHA Architecture Review Committee and the City of Minneapolis Historic Preservation Commission.

Come See Us Sometime

Not long ago, two Milwaukee Avenue residents came home to find a stranger sitting on their porch bench. They asked the man, who was in his 50s and wearing overalls, if they could be of any help. Surprised, he said, “What, do you live here?” When they explained that, yes, this was their house, he exclaimed, “I thought this was a tourist attraction.”

You can be sure, this is no tourist attraction. And it’s not Disney’s Celebration, either. We’re just people who appreciate living in modest historic houses near wonderful neighbors on a quiet street just south of downtown Minneapolis.

To see this historic district, come by transit or park your car and walk to the pedestrian mall. The absence of traffic, the narrowness of the street and the distinct beginning and ending points make it a great place for strollers and bicyclists. The simple rhythm of the gables roofs of houses built in close proximity to the sidewalk creates an intimate sense of scale, once part of urban life, but now largely absent from many American cities.

Available Historical Resources

To access Roscoe’s book, Milwaukee Avenue: Community Renewal in Minneapolis, Hennepin County Library has 2 e-book copies currently available which can be immediately downloaded and read on a computer or mobile device. In addition to Roscoe’s book, there’s this article on the mnopedia.org, Minnesota History website: MnOpedia and the Minneapolis History Collection has “Milwaukee Avenue: A study for saving an old street” from 1973 as well as newspaper clipping files on Milwaukee Avenue and building permit index cards for the houses on the street. There is even building plans for some of the homes on Milwaukee Avenue. These blueprints will eventually be moved to the Northwest Architectural Archives at the University of Minnesota, which is another place for research. For house history, permit index cards can be found from the Minneapolis History Collection.

These pictures are from Mary McDowell, who took them as a photography student in the 1970s. They are unique in that they capture Milwaukee Avenue in the middle of rehabilitation.